In April 2012, then President Obama signed into law the Jump-Start Our Business Start-Ups bill, otherwise known as the JOBS act. In the midst of a recovery from the devastating after-effects of the Financial Crisis, the move was hailed as “a ‘potential game changer’ for fledgling businesses in need of financing.”

In particular, the bill unlocked the promise of equity crowdfunding, an activity which, simply put, allowed companies to raise money from any willing investors via the internet. As President Obama himself put it, by removing these restrictions, the JOBS act promised to allow “start-ups and small business […] access to a big, new pool of potential investors—namely, the American people […] For the first time, ordinary Americans will be able to go online and invest in entrepreneurs that they believe in.”

To be clear, the process of raising money from private investors is nothing new. However, in most countries, including the US, there have historically been rules regarding such an activity that tended to exclude the average person on the street from investing in these deals. In the US for instance, in order to invest in the equity of private companies, individuals needed to be approved accredited investors, or go through regulated middlemen, both of which limited the playing field and created barriers to mass participation. The JOBS act, and the promise of equity crowdfunding, changed all that.

Nearly five years on though, equity crowdfunding continues to remain a fairly limited niche activity. Despite a few success stories, the grandiose predictions of industry-wide disruption haven’t come to fruition. In this article, we take a look at the current state of the equity crowdfunding market in the US, and assess the challenges it needs to overcome in order to live up to its promises.

Growing, but Still Small

The current state of the equity crowdfunding market in the US can be summarized quite easily:

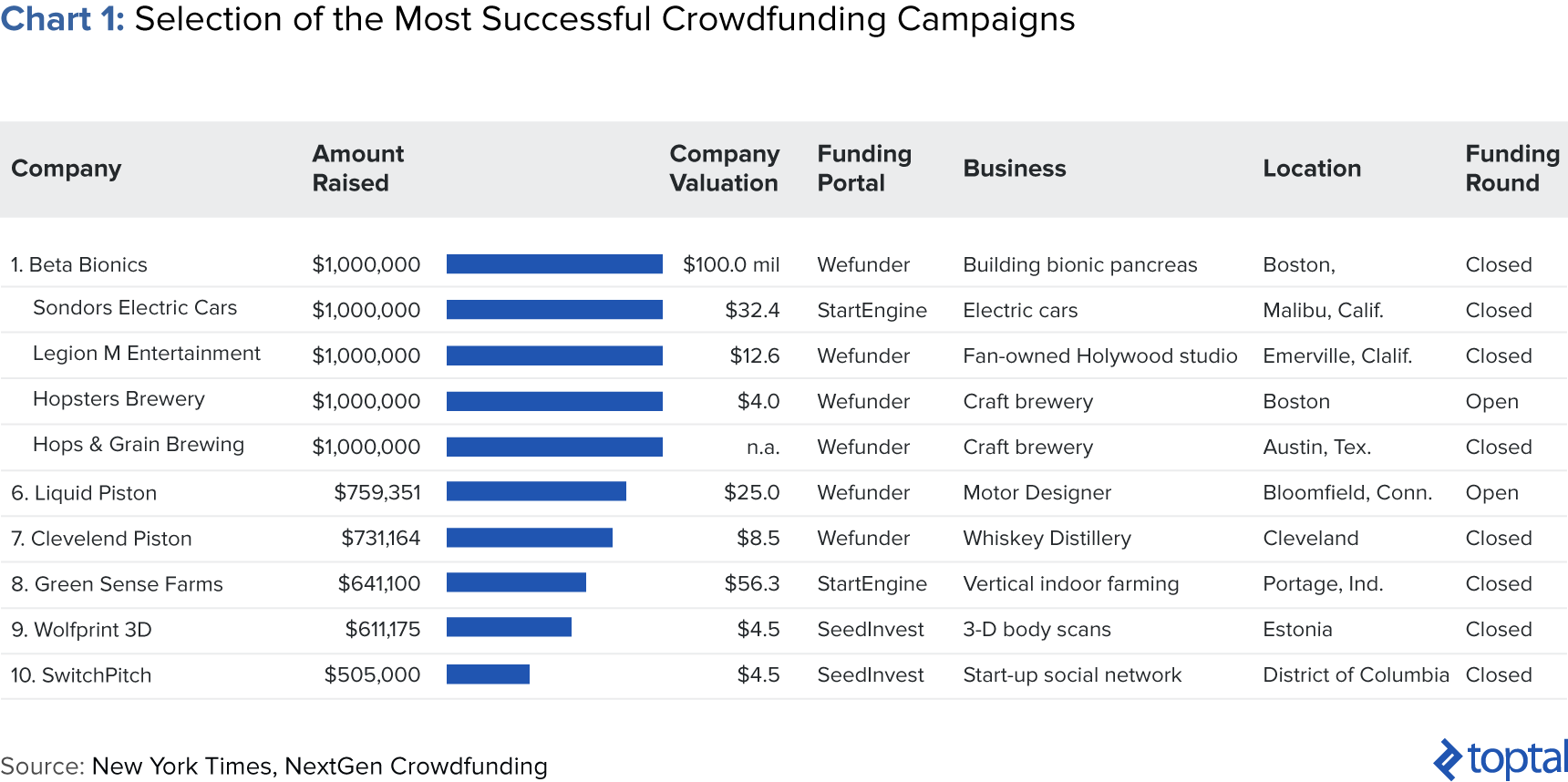

The market continues to be very small. In the last twelve months, there have been several high-profile equity crowdfunding campaigns which have raised non-insignificant amounts of capital for early stage companies (Chart 1).

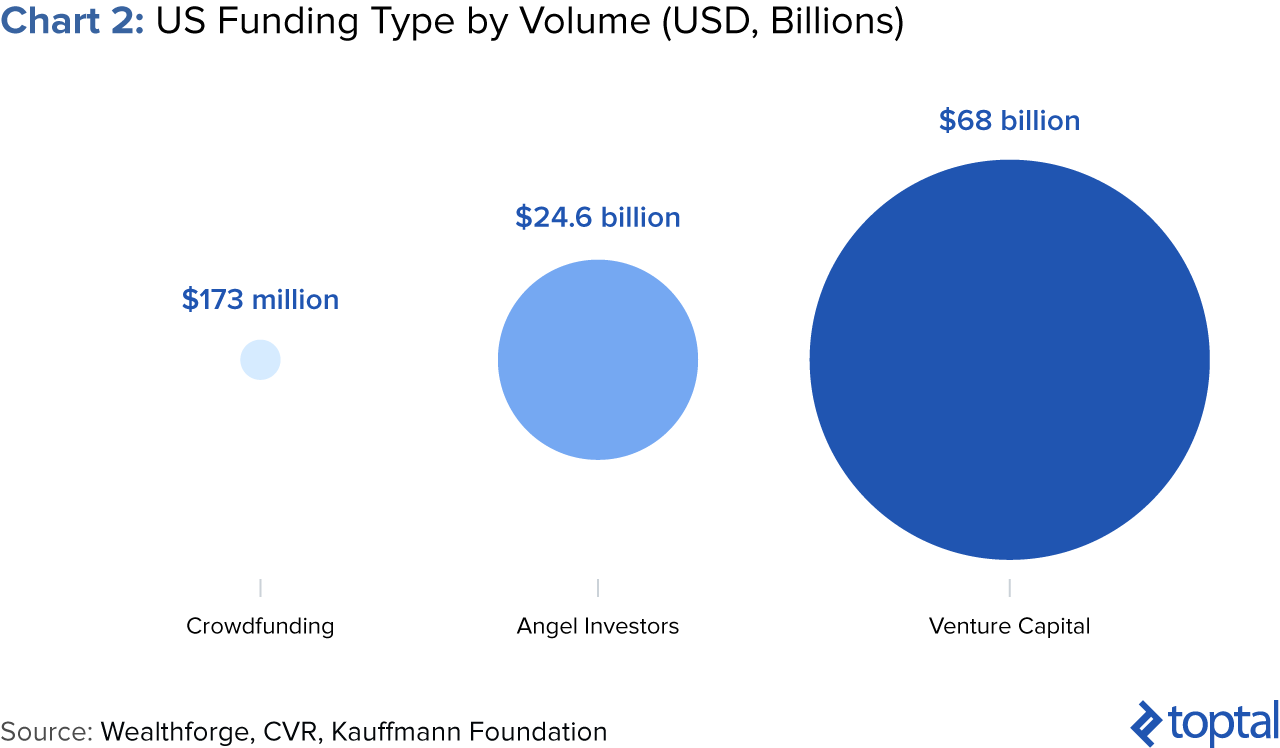

Nevertheless, the biggest takeaway from the data is that the market continues to be very limited in size. While no authoritative studies on the size of the market have yet been completed, the best analysis on the subject comes from a study by Wealthforge, a private capital markets platform. Citing unconfirmed sources from the top US platforms, Wealthforge places the size of the US equity crowdfunding market at just $173 million in 2014 (Table 1).

Comparing these figures to their closest “rivals” reveals the tremendous amount of catch-up that still needs to occur. For instance, even though data is scarce, the size of the angel investment industry in the US for 2015 was estimated at $24.6 billion by the Center for Venture Research. The venture capital industry is of course much bigger, and the Kauffman Foundation puts the size of the industry in the US at $68 billion in 2014.

Turning away from dollar amounts and looking at number of companies raising via these different avenues, the picture is still roughly the same. In its 2016 Trends in Venture Capital Report, the Kauffmann Foundation estimates that the number of firms raising from venture capital funds and from angel investors stood at 7,878 and 8,900 respectively for 2014. This compares to 5,361 for firm raising via crowdfunding as a whole (i.e., including all forms of crowdfunding, not just equity crowdfunding), which means that the equity crowdfunding number is only a small fraction of this (the vast majority of crowdfunding campaigns are either in the peer-to-peer lending space or in rewards-based crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter).

So, data accuracy issues aside, it’s clear that the equity crowdfunding market in the US is a) still extremely small relative to other equity funding sources at the startup and venture stage, and b) is currently used primarily by very small and riskier companies as opposed to higher growth technology startups or more established companies.

Why Is the Industry Still So Small?

Given the above conclusion, the relevant next question would be to ask: Why hasn’t the industry lived up to its potential (yet)? What are the reasons for the market’s still relatively insignificant size?

The answer to these questions is actually fairly straightforward: The principal reason for the market’s limited size to-date is that the JOBS act only finally kicked into effect in May 2016.

In and of itself, this is a surprising outcome. After all, the JOBS act was passed with overwhelming bipartisan support back in 2012. Nevertheless, the SEC, the agency tasked with protecting investors, took over three years to finally publish the details of how the law would work.

Of course, in fairness to the SEC, this was no easy task. As Kevin Harrington put it, “We must remember that the JOBS Act created entirely new methods of selling securities and overturned eighty-year-old securities laws and decades of legal precedent. Because the SEC has to regulate what happens with this new class of capital formation, protect investors from fraud, and enforce the laws against those who misuse it, they need to be very cautious and make sure the rules they pass get it right the first time.”

All of this to say that equity crowdfunding has only really been possible since last year, hence it is no wonder that the market continues to remain extremely small. In fact, as Nathaniel Popper of the New York Times puts it, “The signature element of the crowdfunding law, which allows companies to sell stock to anyone on the internet, went into effect last May, and only about 200 companies have sought out investments to date.”

The Outlook Ahead Is Murky

Reading the above, and returning to our original question of whether equity crowdfunding has lived up to its promise, one might quickly conclude that it is too early to tell. And our assessment would be the same. Nevertheless, despite the above, we foresee a number of challenges the industry will have to resolve before we can expect it to see significant growth.

Beware the Frauds

The first reason why we remain cautious on the industry’s immediate growth prospects is because it is likely that the market will soon be rocked by high-profile scandals involving investor fraud.

Ryan Feit, CEO of SeedInvest, put it nicely in an article following the publication of the Title III Equity Crowdfunding rules (the final rules established by the SEC on equity crowdfunding):

“Although Title III has significant potential, there is a lot that could go wrong. It will be up to platforms themselves (ie. [sic] “The Gatekeepers”) to ensure that they don’t screw-up [sic] the opportunity. First, platforms out there which merely act as listing services could increase the likelihood of fraud and failure which is problematic in the medium-to-long-term [sic]. Selling securities is not the same as selling a couch on Craigslist and they should be handled very differently. Second, investor education will be critical given that investing in private companies is dramatically different than investing in public stocks. Platforms must ensure investors know upfront [sic] that private companies are risky, that you must diversify, that there will be little or no liquidity and that you should only allocate a small percentage of your overall portfolio to early-stage companies. If platforms fail to do this there will be lots of unhappy investors. The opportunity is real, but so is the risk if the industry doesn’t handle it prudently.”

And unfortunately, this seems to already be happening. In 2015, the SEC shut down Ascenergy, an oil and gas industry startup that had raised $5 million on crowdfunding sites from more than ninety investors. According to the SEC, “[Ascenergy] did not appear to have any of the expertise or contacts in the oil industry that it had claimed in its online material. By the time Ascenergy was stopped, the company had already spent most of the millions of dollars it [had raised from] investors. Much of it was used for the personal expenses of its founder, paying for ‘fast-food restaurants, Apple stores and iTunes, dietary supplements and personal care products.’”

Situations like the one above are likely to continue to happen. In fact, CrowdCheck, a startup focused on providing transparency and investor protection for crowdfunding and online investments conducted a survey on compliance in the industry, and found that “almost none of the companies that have been listed so far are fully in compliance with even the basic rules set down by the Securities and Exchange Commission. About 40% of all companies, for example, did not get their financial results audited or certified, as is required by the rules, CrowdCheck found. The lower regulatory barriers for crowdfunding mean that the S.E.C. does not individually check whether companies are following the requirements.”

For an industry that is still in its infancy, early setbacks in the form of headline-grabbing cases of fraud are likely to severely hamper the industry’s growth prospects in the short-to-medium term.

Most Investors Will Lose Money

The second reason why we remain cautious on the industry’s immediate growth trajectory is that, fraud aside, early equity crowdfunding investors are likely in for a cold shower. After all, investing in startups is a risky business. The US Department of Labor estimates that the survival rate for all small businesses after five years is roughly 50% (Chart 4).

For high growth technology startups, the picture is even bleaker. A study co-authored by Berkeley and Stanford faculty members with Steve Blank and ten startup accelerators as contributors, found that within three years, 92% of startups failed.

The above therefore means that in most cases, investing in startups means losing one’s money. Sophisticated investors of course already know this, and several theories regarding optimal portfolio allocation and distribution have been developed. Peter Thiel for instance popularized the notion of the Power Law with relation to startup investment, and Fred Wilson famously outlined his views on the “VC batting average.” But the point is that these are sophisticated and knowledgeable investors, who have over time developed and refined their skills and networks to achieve success. But most equity crowdfunding investors likely are not, and will therefore probably see poor returns on their investments.

In the UK, for instance, a market in which equity crowdfunding has been legal for over four years, a recent study found that “one in five companies that raised money on equity crowdfunding platforms between 2011 and 2013 had gone bankrupt. Investments of £5m were made in companies that had ceased trading or were showing signs of distress.”

Ryan Feit of SeedInvest again puts it nicely: “[I’m] less worried about outright frauds and more concerned about companies that [are] unlikely to ever pay off and that were not giving investors enough information to judge them.”

The above in fact highlights an even more concerning issue. Not only are startups already incredibly risky, but given the relatively low level of knowledge and understanding of startup investing by equity crowdfunding investors, startups seem to be taking advantage of this. Marc Leaf, a lawyer at Drinker Biddle, said that “so far many companies were asking for investments on terms that few real venture capitalists would accept.”

A commonly cited criticism of equity crowdfunding rounds is the unfavorable rights the investors receive. In the UK for instance, Crowdcube, the country’s largest equity crowdfunding platform, has come under criticism for putting investors “at significant risk of ‘aggressive’ dilution—when a company offers new shares at low prices, vastly reducing the value of stock—to the detriment of existing shareholders. In most pitches on Crowdcube, all but the largest investors receive ‘Class B’ shares. They have no voting rights or contractual protections to prevent dilution, such as ‘pre-emption rights,’ where existing investors must be offered shares in a company before they are made available to anyone else.”

To counteract this, some platforms, such as Seedrs, adopt a “nominee” structure, whereby “the platform acts as a nominee shareholder on behalf of investors, managing the investment for them, including voting.” But even this falls short of the mark. Jeff Lyn, Seedr’s CEO, admits that “‘on several occasions’ it has already waived pre-emption rights on behalf of its investors, particularly when professional venture capital groups have looked to be involved in new rounds of funding a company.”

Questionable Value Proposition

All of the above strongly points to high failure rates and poor returns in the immediate term. And no doubt the consequence of this will be that equity crowdfunding investors will turn to more experienced and knowledgeable third parties to perform deal and company evaluation and assessment. But who should take on this role?

Some platforms have already begun to take responsibility for screening investments before offering them on their platforms. SeedInvest, for instance, “over the last two years has turned away dozens of companies that wanted to raise money from investors on his site. Some of the companies had what seemed to be clear red flags for investors, but later showed up on other crowdfunding sites, where they have raised hundreds of thousands of dollars from unsophisticated investors.”

Other approaches have been proposed. Ryan Calbeck of CircleUp has proposed a shift to what he calls “marketplace investing,” where “the marketplace is a conduit for the right investors and entrepreneurs to come together. Individual investors can invest alongside institutional investors in these marketplaces. To [Calbeck], that’s a more exciting vision of marketplace investing than the original contemplation of ‘crowdfunding.’”

Nevertheless, notwithstanding the question of who ends up taking on the role of “gatekeeper,” the more general point is that if gatekeepers become the norm, the original thesis of equity crowdfunding is called into question. After all, the essence of it all was to remove friction and middlemen and allow anyone to invest. Introducing gatekeepers goes against that. In the same way that investment banks and brokers only work with clients that fulfill certain criteria (which usually involve a minimum net worth or amount of investable capital), it wouldn’t surprise us that these future “gatekeepers” of the equity crowdfunding industry begin doing the same. And if that were to happen, we’d essentially have gone full circle.

That’s why many equity crowdfunding evangelists are against this idea. For example, Nick Tommarello, co-founder of Wefunder, mentions “that his site had to be sure companies were following all the rules. But he said he did not think […] that it is the place of crowdfunding sites like his to argue with companies over their proper value. That, he said, would defeat the purpose of crowdfunding. ‘It’s not my job to be a gatekeeper,’ he said. ‘It’s my job to be sure everyone knows the risks they are taking and that they have all the information they need.’”

The Need for a Liquid Secondary Market

Turning further ahead, another problem that this nascent market is likely to soon face is the lack of a liquid secondary market. Equity crowdfunding investors will at some point need to cash out of their investments. Given that most startups take years before a sale or other type of liquidity event occurs, unsophisticated investors who are uncomfortable with their money being locked up for 7-10 years will likely shy away from the asset class as a consequence.

The SEC itself is aware of this issue, and already back in 2013 had recommended that “the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission should facilitate and encourage the creation of a separate U.S. equity market or markets for small and emerging companies, in which investor participation would be limited to sophisticated investors, and small and emerging companies would be subject to a regulatory regime strict enough to protect such investors but flexible enough to accommodate innovation and growth by such companies.” However, to-date, the agency has yet to give the green light on the proposal.

In the UK, Crowdcube has already announced its intentions of “creating an environment for shareholders of any private UK company to sell their stake.” In the US, Seth Oranburg, a visiting professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law, is also pushing for what he says is a way to accelerate the process: “Have crowdfunding portals hire analysts who would provide potential buyers with information about companies’ prospects and valuations. That way […] a secondary market will be a much safer environment for unsophisticated small investors—and much more attractive for regulators to approve.”

Were such a market to eventually emerge, it would still face some of the challenges we mentioned above. Unsophisticated investors would likely be faced with valuation challenges when it would come to selling their shares. And fraudulent selling practices would likely emerge to harm secondary buyers. In the same way that trading on the public markets is a highly regulated activity, a liquid secondary private market is most likely going to follow a similar path.

Practical Tips on Investing in Equity Crowdfunding Campaigns

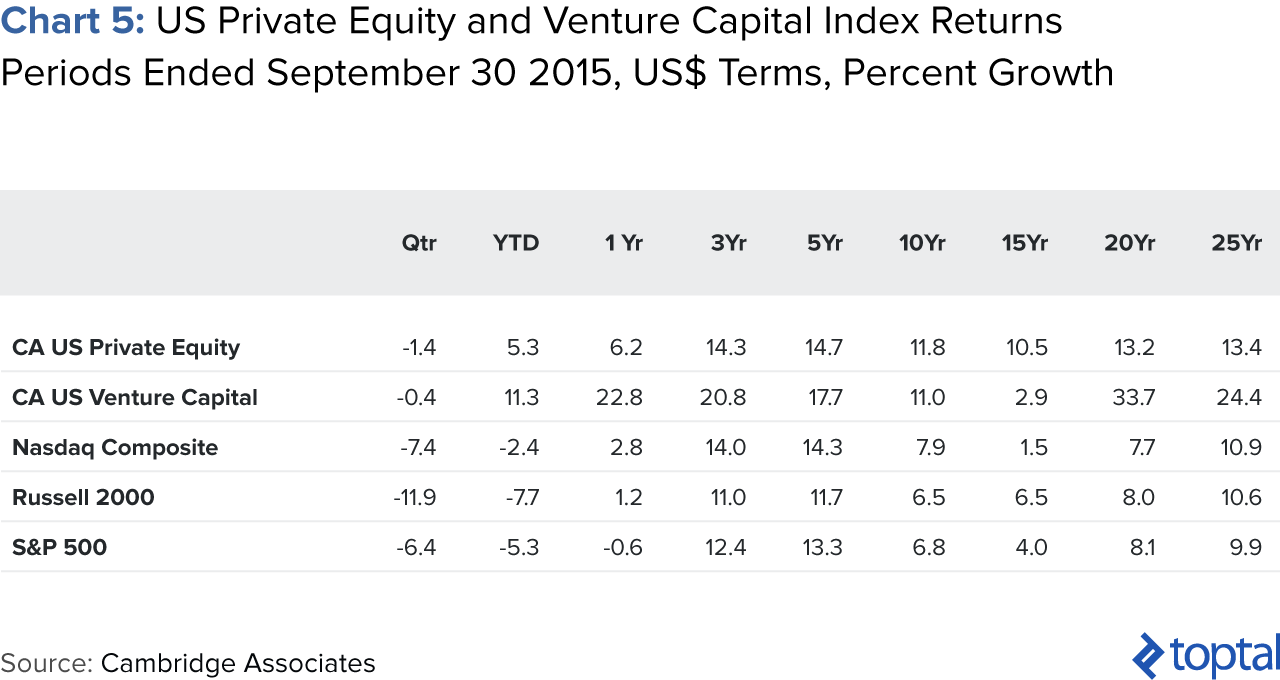

Despite all of the above, a smart, focused, and thoughtful strategy of investing in equity crowdfunding deals could work out quite well for investors. After all, as an asset class, venture capital has some pretty decent returns. Cambridge Associates for instance found that its U.S. venture capital index outperformed other indexes over most time periods (Chart 5).

But there is no doubt that investors need to take care when choosing to put their money to work. Below are a few practical tips to maximize your chances of success:

- Diversify your portfolio. A time-tested practice amongst investors, portfolio diversification is key to ensuring that you doesn’t have too much single-name exposure to one asset. There are obviously techniques for portfolio diversification which include diversifying across sectors, across business models, across funding stage (which wouldn’t apply in this case), but whatever the case, make sure to have a nicely balanced and diversified portfolio. Here’s an interesting article to get you started on the topic.

- Don’t invest too much of your personal wealth. Limit your own personal exposure to this asset class. Given the highly speculative nature of seed/venture investments, you should limit your personal net wealth allocation to the asset class to only a small part of your overall portfolio. Exact amounts will vary on financial circumstances and your risk appetite, but a good rule of thumb could be 10% or less. This article delves into the topic a little more. It in fact suggests that most “large asset pool managers would like a 5–10% allocation to venture capital because of its past returns and anti-correlation with other asset classes”.

- Do as much diligence on the investment opportunities as possible. Understand the business model. Try and speak with the company executives. Understand the market. Look at the company’s financial performance and traction to date. Does the founding team have solid backgrounds? Do the founders complement each other? Asking lots of questions is always better than not. Perhaps focusing at first on a business model or industry which you know very well would and in which you have an “unfair advantage” would be a good way to start. Due diligence on venture investment opportunities is an art, not a science, but here is an interesting article by one of the smartest venture investors around on the subject.

- Vet the platform. Make sure that the platform through which you are investing is legitimate. Have they had successful campaigns before? Reach out to other investors to see what their experiences have been with the platform. Does the platform perform any of their own due diligence on the opportunities? If so, what are the criteria? Read through the terms and conditions very carefully. This article goes into this topic further.

Despite the Challenges, the Cause Is Noble

As we’ve outlined above, we have significant doubts on the market’s prospects to fundamentally disrupt the funding landscape for small businesses any time soon. Cases of fraud, poor returns, a lack of exit alternatives, and a questionable value proposition all point to subdued growth over the short-to-medium term.

And putting these aside and taking a step back, it’s probably worth asking oneself if the average person on the street, the very person that the JOBS act was intended to target, is really even interested in investing in such a risky asset class. Yes, equity crowdfunding does “democratize” the field and allow anyone, not just the rich and powerful, to be angel investors and venture capitalists. But does the average person on the street really want that?

However, despite the challenges, we’d like to argue that equity crowdfunding is a noble cause worth fighting for. It may have its challenges, and its true worth may be less than what the hyperbolic market evangelists initially claimed, but at its core, equity crowdfunding is about fairness and equal access, two things worth striving for.

After all, returning to the status quo of only “accredited” individuals being allowed to invest in private companies doesn’t seem right. Allowing anyone, not just “sophisticated” investors, the right to invest in the next Snapchat or Airbnb feels like a fairer situation, albeit one that involves significant financial risks for those who choose to partake in the market.